Clinically testing sun protection products before they can be brought to market has never been a straightforward process. It’s a highly regulated category with a multitude of factors and claims that need to be tested, including Sun Protection Factor: (SPF), UVA Protection Factor (UVAPF), Critical Wavelength (CW), and Water Resistance (WR), to name a few.

Fortunately, these procedures are globally harmonised by the ISO (International Organization for Standardization) standard.

How do you test for sun protection factor?

The current in-vivo SPF test protocol used in Europe (ISO24444/2019) was created by a team of international experts in the International Standards process and is widely used to support labelled protection claims or in-market control.

However, despite so many tech advancements in the personal care industry in recent years, testing Sun Protection Factor (SPF) still needs to be evaluated on the skin of human volunteers in an ‘in-vivo’ test.

Although this test has been the best option until now, there are ethical issues to consider because erythema (skin reddening) is currently used as the method to assess the UVB exposure.

To simplify this: the SPF value given on a bottle of a sun protection product must be determined by burning the skin of human volunteers with UVB radiation.

Although this current ‘gold-standard’ test for sunscreen products sold in the EU has long been the most reliable option, it is also invasive, time-consuming and expensive, and has the aforementioned ethical concerns.

Plus, it’s also not entirely accurate because the sun cream is applied to the skin by humans rather than machines, which can affect the end outcome, and the level of sunburn on the skin is also assessed by humans.

A new in vitro option: Double Plate Method

For more than 30 years, members of the trade association Cosmetics Europe have been working on an in-vitro alternative to this test, called the In Vitro Double Plate Method (DPM).

The ISO Sun Protection Working Group (ISO/TC 217/WG 7) has now unanimously recommended that this new method – along with another method called the Hybrid Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (HDRS), could be advanced to the Final Draft stage of the ISO development process.

This new DPM test is now in the final-approval stage and expected to be published as the official international standards in early 2025. Manufacturers and other test laboratories will then be able to test the efficacy of sun protection products using these internationally recognised standards.

We spoke to Cosmetics Europe’s director for technical regulatory affairs, Gerald Renner, to learn more about this scientific breakthrough for the beauty and personal care industry…

Cosmetics Design-Europe (CDE): Can you explain more about why there was a need to create an alternative to the current ‘gold-standard’ SPF testing method?

Gerald Renner (GR): Sun protection claims are not necessarily the same as a skin moisturiser claim. If these claims are not correct, there can be a real health issue.

For more than 30 years. Cosmetics Europe members (including major European sun-product manufacturers and contract testing laboratories), have been working on these test methodologies to make sure that there is an objective, reproducible testing that allow those standardised testing methodologies.

We wanted to create a level playing field between the companies. And as I said, if there is something wrong with your SPF claim, there could be some harm done.

If you look at a way that the SPF testing is done today, it has some limitations because it’s a test protocol that was developed more than 40 years ago.

Currently, to test SPF, you take human volunteers, irradiate them with UV light on protected and unprotected skin, and then you can see at which UV doses the skin gets sunburned.

From that you can calculate the sun protection factor – as the protected skin will get the sunburn at a later stage compared to the unprotected skin – and from that ratio you can calculate the SPF.

So, first and foremost, there's an ethical concern with this test method.

Back in 2006, the European Commission made a recommendation on sun protection claims and labelling and said that there should be standardised test protocols and preference should be given to in vitro tests. Why? Because, if you test with human volunteers, you expose them to UV light to the point of burning the skin, which is exactly what dermatologists say shouldn't be done.

CDE: Can you tell us more about the new method you’ve been working on – the In Vitro Double Plate Method? What are the advantages for sun care brands and consumers?

GR: For 20 years, we have been working on a method that would be able to test suncare without human volunteers, via an in vitro method. Now we are at the point where the method is in the last stages of ISO approval.

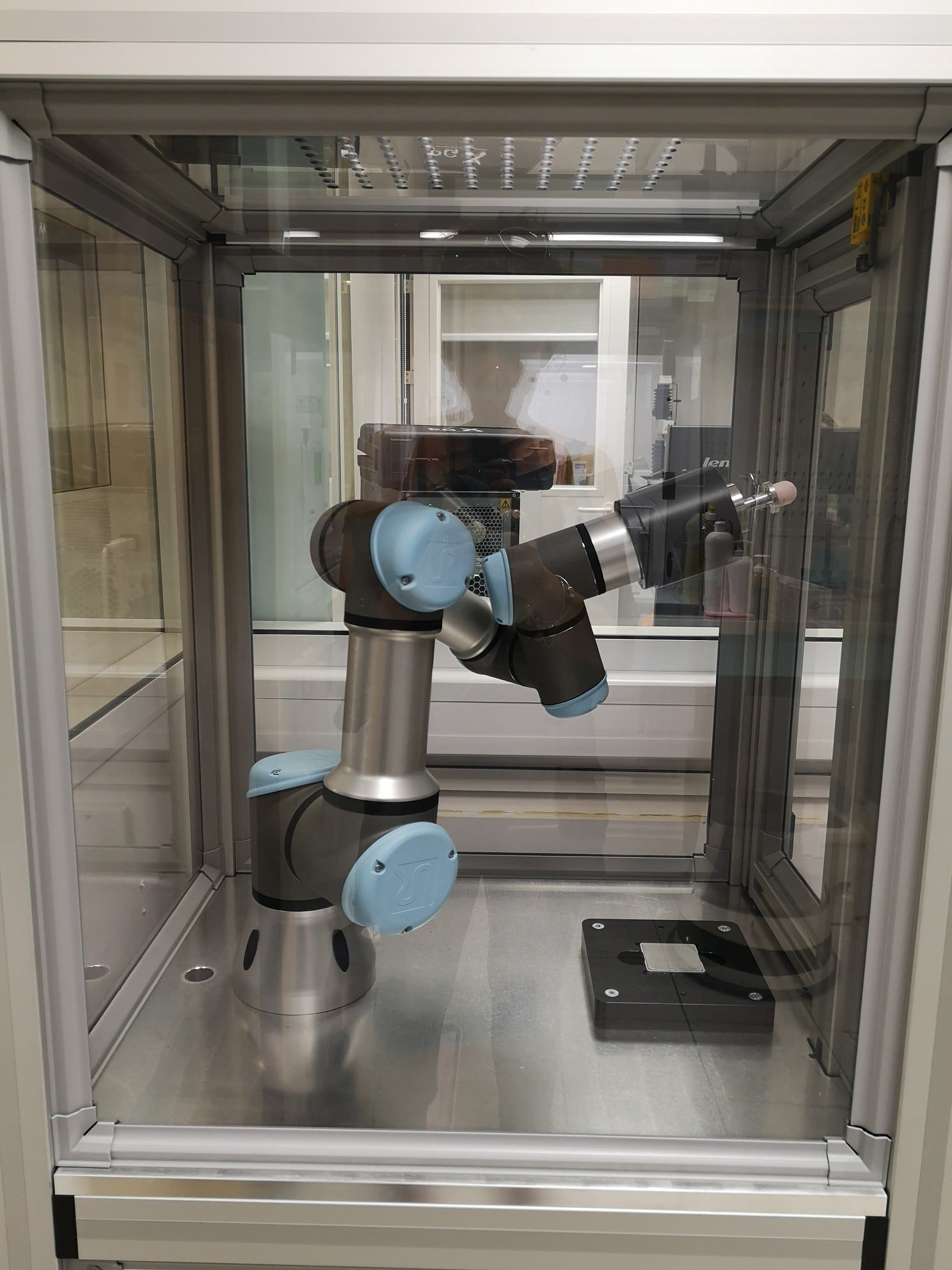

We are very excited because this could become an alternative to human testing. This has advantages in that we don't need to burn the skin of human volunteers. It also takes out some of the inherent variabilities. When you do the in vivo (human) test, there are several other ‘human’ factors in there. It's a human who applies the product on the skin, and we know that how the product is applied really influences a lot the actual SPF that you get. When two different people apply the same product onto the skin, there will be a difference, even if it’s slight. So, to standardise this is extremely difficult. We solved this by using a robot to apply the product – it can follow a pattern with a specific pressure that doesn't change.

We have replaced the human volunteers with ‘plastic’ plates. It’s actually two different types of plates combined that predict how the skin feels. First, we tried with one type of plate, but that it didn't work. The second was close but didn't work either. But we found that when you combined the two results it worked well. That's why it's called the Double Plate Method.

There are other issues with the current testing method. For example, to assess the results, the person comes back to the testing lab and somebody needs to assess whether the skin is burned, and this can be very subjective. These are trained assessors, but there can be differences in opinion.

There's also the limitation that the darker the skin of the human volunteer, the more difficult it is to see the actual erythema. Whereas for the plate, there is no colour. You also can’t do human testing in the summer months because people are already tanned, but this new testing method can be done at any time of the year. Plus, we can also test many more products in the same amount of time.

Finally, this new method is also significantly cheaper. There's an upfront investment of the robot to apply the sun product, but the other materials are something you probably have in a testing house already. These plastic planes don't cost a lot, so the testing is very cost-effective too.

So, these are all advantages. This new test allows us to overcome some of the limitations of the previous one.

CDE: Can you tell us more about these ‘plastic plates’? How can you be sure that they replicate human skin?

GR: We have tested hundreds of products. We already have the in vivo results from the human testing, and we validated our method with hundreds of products to see if we got the same results. And it's a very, very good correlation.

A challenge was how we could make sure that the plate really mimics the skin. For a long time, we tried different types of plates, and as I said, none of them completely worked alone, but when we combined the data from two different plates, all of a sudden it fell into place.

We needed to mimic the skin, but no single plastic plate could do that. It was all about the surface: we needed to mimic the surface of the skin on the surface of the plastic plate. There were different ways to do this, via sandblasting or moulding the plastic plate. On their own, neither method could mimic the skin, but, when we took those results together – sandblasted and moulded – all of a sudden, it mimicked the skin quite well.

Also, when it came to reading the result for the in vivo (human) test, where the person says: “yes, this is a sunburn”, or “no, this is not a sunburn”, we basically have a machine, a spectrophotometer, that measures irradiation. So, it is objective, not subjective.

The ‘plastic plate’ is in fact a little square that has a surface that’s treated to mimic the skin. It has grooves just like the skin has, so the product fills these grooves, as it would on the skin.

CDE: Now you’re waiting for ISO approval and this will most likely become the new ‘gold standard’ for testing SPF products in the EU. Is there still more work to do? Where can this go next?

GR: We expect that this is not only going to become this method of choice for the sun care industry, but also competition authorities. There are a lot of benefits we believe will come with this.

The next step is for us is to develop a method that measures UVA protection at the same time (as it is currently measuring SPF rating; UVB protection), but we haven't validated that step yet. So, companies will still need to do two tests for UVB and UVA right now, but in the future, this is likely to become one combined test.

In fact, this should go into the first revision of the method, which would usually happen within no more than five years. Every ISO method needs to go through a mandatory revision to see if it is still valid every few years. So when this method comes out in 2025, there will need to be a revision before 2030, by which time we will be ready with the UVA, maybe even earlier. We might even trigger a revision earlier, but I don't want to promise this.

Currently, UVA testing can already be done in vitro, and this is another relatively cheap and simple test, but of course, doing it all-in-one would be more convenient.

There are also other sun protection tests for us to consider. For example, the ‘water resistance’ claim. As for water resistance testing today, you still need to sunburn consumers, because the only method that exists is the human volunteer method. You measure the SPF before you put them into jacuzzi, and you measure the SPF again after this.

We are also currently working on an in vitro method that can measure water resistance, but we are not as close as we are to achieving the UVA test. We already have the data to do the validation for that, but with this (water resistance) there is some very promising work ongoing and if things go as well as they have done, we could also be able to measure water resistance via an in vitro method.

I should also mention that there is one galenic that we haven't validated yet for the DPM SPF test. This is dry powder sun protection products. But all other formats – emulsions, mono-phase oils, hydroponic sprays – are all validated, and all types of filters too.

I think people should really get to know this method now because it will soon be a reality. We believe that it will be widely used and both by those who want to support a claim, but also by those who will test and control a claim. I'm maybe a bit optimistic, but my prediction is that this will become the method of choice.